The Dichotomy of the World

Every visit to India is an opportunity to revisit the core dichotomy of my life: leaving rural India at a young age and slingshotting into a higher quality of life and opportunity bracket in the United States. This is my first time visiting in over three years due to the pandemic. I wrote most of this piece while on a train from the capital city of New Delhi to my native village near the Siwan district in the state of Bihar.

The Transition Phase

I boarded the train last evening at a chaotic New Delhi Railway Station on a roughly 16 hour journey into the interior of the country. Train 12554, more commonly known as Vaishali Express, is named after the ancient sixth century city near the train’s terminus. This train is among the select few designated as "superfast," receiving priority status due to its importance as a vital link between the capital and Bihar which carries over two thousand passengers over 24 hours and 1100 miles.

It’s now morning: fellow passengers are starting to get up, the chaiwala has done several rounds through the car and the morning shift ticket inspectors are now making their checks. After a restless night due to jet lag, I pack up my bedding and adjust my seat back from a lie-flat bed so I can comfortably sit and enjoy the view outside. This journey brings back the memories of home, as I leave behind “modern” India and step back into this part of the country. The transition from the West to East occurs on a plane, but the true dichotomy of India reveals itself as my train crosses into the Purvanchal region - a collection of districts from western Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh states. The polluted air and hustle of New Delhi gives way to the serene Ganges floodplains, evoking memories of home. The scenery outside fades into a patchwork of farms and the small paths meandering through them. The recent monsoon rains, the lifeblood of this region, have provided relief from the heat and yielded a verdant growth of rice paddies. Cows and water buffalo graze, with the occasional shepherd nearby, phone and bamboo stick in hand. Coal-fired brick kilns, known as "chimneys," lay dormant, waiting for the harvest to end before churning out their winter round of bricks for the construction boom.

This journey reminds me of the divergence in my life trajectory compared to the average person from my native region. My relatives support me without knowing me day to day, their lives marked by a different kind of struggle as the country grows, the middle class expands, and industrialization progresses.

Signs of Progress

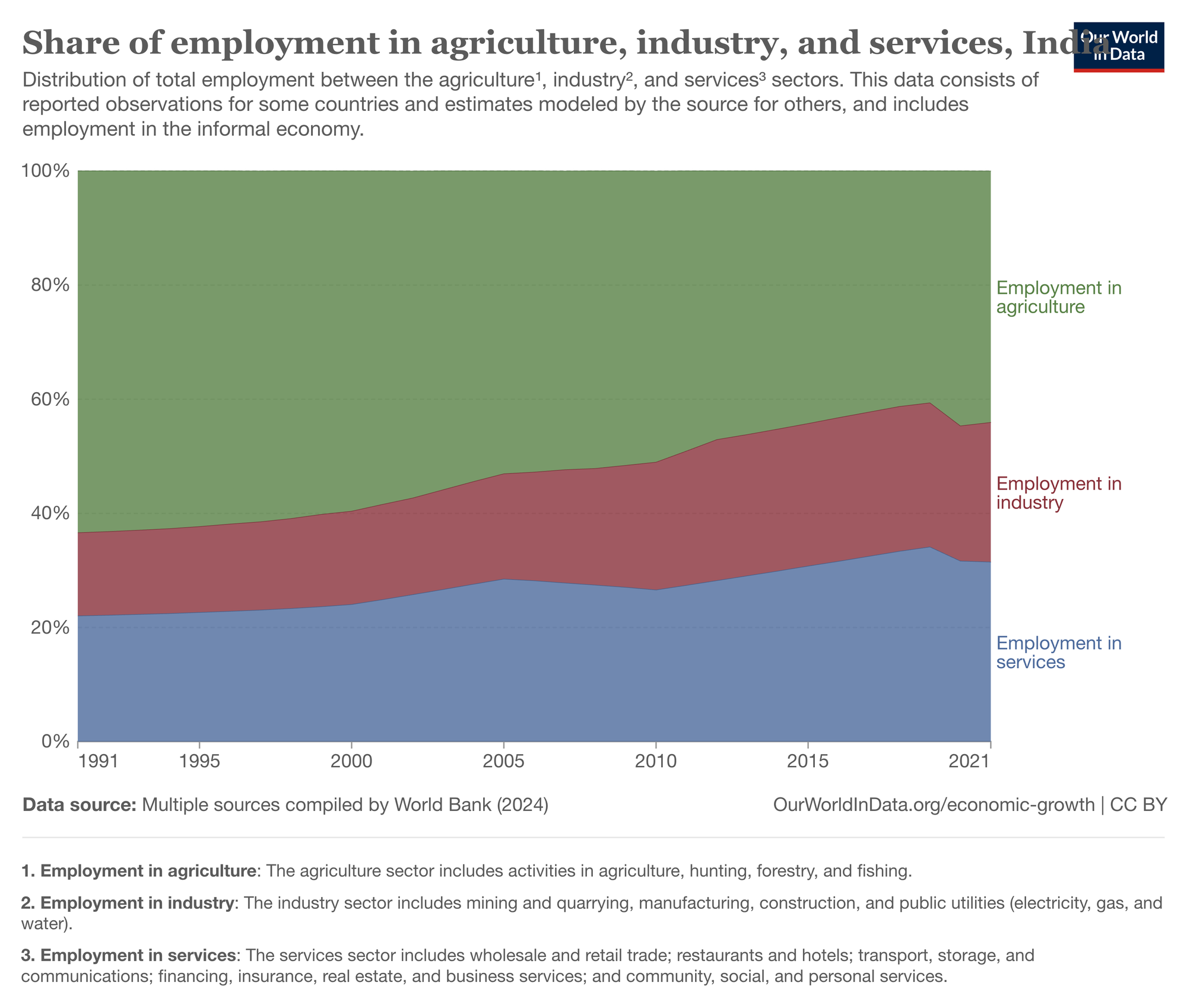

As the train zips by, I notice the overhead electric cables – a new addition to this route, now fully electrified and dual-tracked. Everywhere I look, there are signs of progress. The train coach itself has been modernized with better sound insulation, quieter air conditioning and USB charging ports. Incandescent bulbs are replaced with LED lights and improved toilets have an onboard sewage treatment system and tanks. Outside, the world of subsistence farming has given way to new businesses and services where sharecroppers farmed. Family incomes have doubled or tripled in the last decade although I’m sure the average family earns as much in a year as half my monthly rent back in California. New villages and towns dot the route, complete with paved roads and signage that didn’t exist five years ago. Gone are the at-grade railroad crossings, replaced by underpasses and flyovers, all packed with SUVs and heavy duty semi tractor-trailers instead of the historical herd of motorcycles, tuk-tuks and farm tractors. Once reserved for larger towns and cities, cell towers now dot the landscape almost every few kilometers, as do solar panels on rooftops.

The train stations I pass through have also been modernized. British-era heavy stone arches are now augmented with corrugated metal roofs, solar panels, LED lighting, and digital signage. Some stations even have WiFi and there is more order than chaos compared to before. These are all signs of India’s economic growth despite the pandemic. On my return journey I’m actually flying which wasn’t even possible due to a lack of airports in the region.

Through all of this, the train and the Indian Railways itself is a microcosm of the country and progress. As a government-owned company, it has federal zones, its own bureaucracy, education system, and housing for employees. It offers everything from AC First Class to general/unreserved seating, symbolizing both technical progress and the common man. It moves at a massive scale across all regions of India, reflecting its diversity in the names of the trains and the multilingual station signs. The vast redevelopment and systematic growth is a reflection of the wider growth in the Indian economy and changes in society.

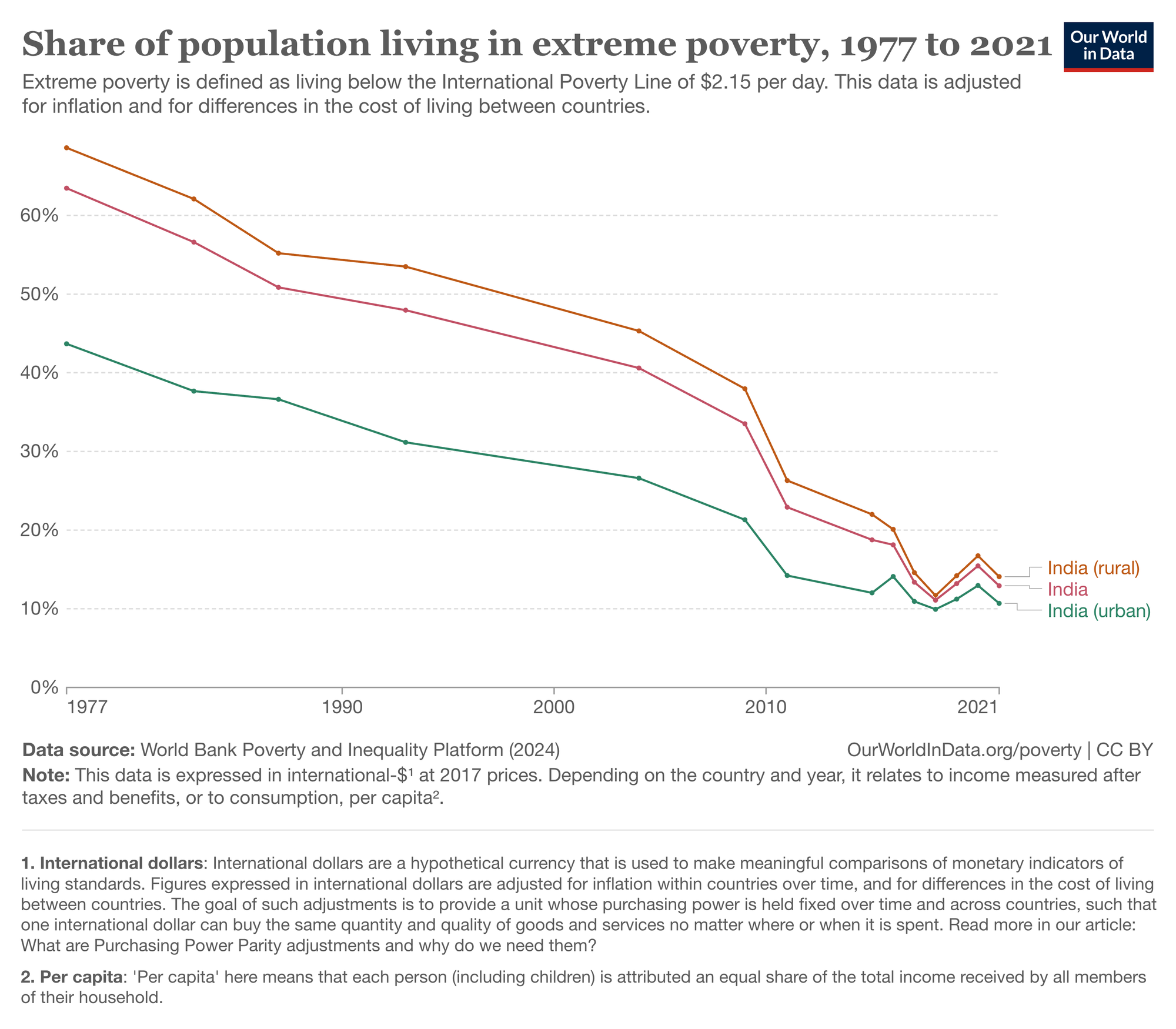

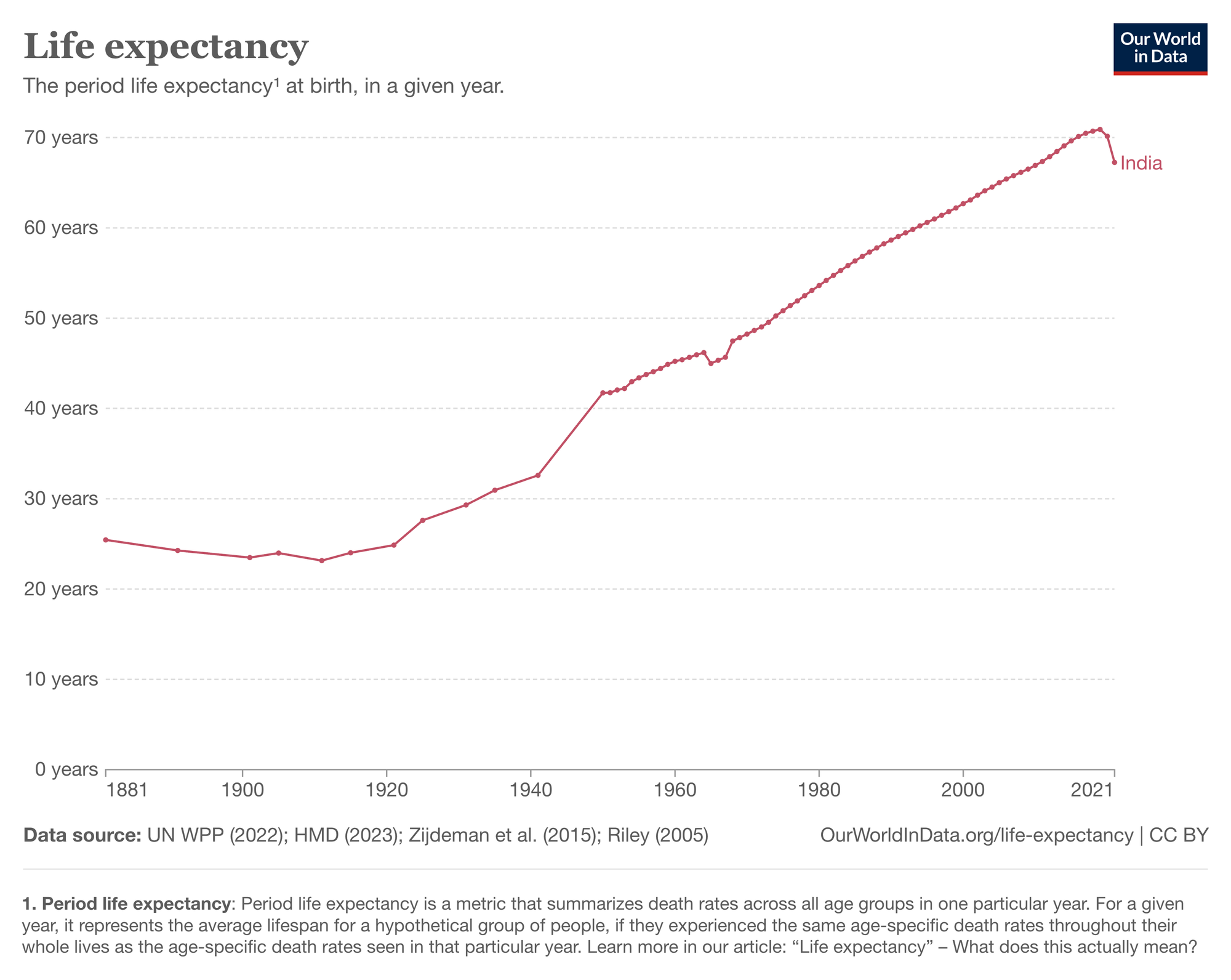

I was interested in seeing the numbers so I wanted to share some statistics about India over the last several decades of progress.

As the train zips through the northern Indian countryside, my mind wanders freely across time and space. As I mentioned, these train journeys have always been the "in-betweens" for me, bridging significant phases of my life. It’s a reflection on my origins, growth and the progress I have witnessed since stepping on this same train almost 20 years ago before my departure for the United States. It’s a journey that forces me to consider my identity, my heritage, and my responsibilities.

My Origin Story

I was born in a relatively lower middle-class family in rural India, but we were upper caste, which meant there was a certain deference to us in the village. I don’t know much about my family tree but my paternal grandfather was the first in his family to get an education and landed a prestigious government job as a bank manager. He educated his younger brother (my granduncle) who eventually became a lawyer and established a quite successful private practice in Siwan. My maternal grandfather was a prominent landowner and worked as a clerk in a British-era sugar mill. His parents and grandparents before him were administrators in the British Raj, and his childhood stories are full of elephants, indigo farming, and encounters with British officers on horseback. As a kid, whenever I passed the sugar mill where he worked, I would look up in awe at the tall smokestacks and heavy machinery; the place felt out of place surrounded by verdant farmland and a nearby stream. I later learned it was imported from Java by the British in 1903 to process all the sugar cane grown in the region. It was the first sugar mill in India. In the next generation, my dad got a PhD and had the opportunity to come to America, a moment that perhaps defined my life the most: it ensured I would be on the other side, the Western world, the developed world, and have access to opportunities out of reach for my ancestors.

A Product of Prior Generations

When I enter India, I switch to Hindi, and when I enter Bihar I speak in the native Bhojpuri. I studied so much American history growing up, yet being here reminds me that my history is here. Unlike my classmates who have grandparents or great-grandparents who immigrated from Asia or Europe, or a friend who can trace his lineage to the Mayflower, I have no such stake or claim in American history. As much as we put rugged individualism on a pedestal in America, I stand on the “shoulders of giants” who came before me, like my parents and grandparents. My hard work and efforts have less bearing on my life than the starting advantage accrued by my forebears. This reminds me that the greatest impact I can have will be felt two or three generations from now. I won’t know them, but my actions today will greatly impact their lives. This, in turn, forces me to consider legacy as a factor in decision-making. We speak a lot about individualism and self-reliance, instilled in me by growing up in the American Midwest—the “do it yourself,” the “self-made man”—but really, I am a product of hard workers and the right collection of opportunities, and it’s my duty to carry this forward.

Growing Up as an Immigrant

On the other side of this divide, I grapple with growing up as an immigrant kid in the 2000s and 2010s. Modern life in the United States isn’t always ideal; it often means missing out on aspects of the community-based village lifestyle my ancestors lived. Although they faced famine and starvation as empires vied for control of India, societies in the Indian subcontinent featured strong communities and well-established family life as a bedrock, arguably yielding a more nurturing environment than the rugged individualism promoted in the West. Social media has only exacerbated divisions, as seen in the 2016 US election and the rise of algorithm driven content and echo chambers.

Growing up in the United States, I missed out on the holidays and festivals that form a significant part of my culture and heritage. These celebrations were a time for extended family to come together, but I spent most of my time away from my cousins and extended family. In school, I was often the only Indian kid, and being Indian came with the expectation of being smart—the stereotype of the “model minority.” My peers of Asian origin have also struggled with this role that has come to be expected of us.

On the flip side, I often wonder if my great-grandparents would approve of my Western lifestyle and value system, which can conflict with those back home. When I visit India, I am mindful of being a good visitor, taking extra care to respect local traditions and avoid offending anyone. Elders in rural areas often ask me questions about basic technologies, which can seem silly but highlight the gap between our worlds.

It’s a tradeoff, though—while my cousins envy the air conditioning and same-day shipping available through Amazon in the US, they are gradually closing the gap. These differences underscore the contrasting realities of my life as an immigrant, straddling two worlds with distinct lifestyles and expectations.

Common Humanity Bonds Us

India has always been changing, but perhaps because I’m older now, perhaps because I have seen more, it makes me pause and think—how can I do something? Part of why I studied engineering was to influence and bring about positive change in parts of the world which do not have the same level of access or resources as the United States.

When I was younger, I remember seeing a kid panhandling at the station and crying because I wasn’t allowed to give them money. The struggle is real—I see people struggling, loading fruits on a cart in the village market to walk 10 hours in the heat so they can make enough to put food on the table. Yet you see people engaged in good honest work—from the lady sweeping the floor at H&M in the Delhi mall who said she was working to save up for better education for her kids. You hear stories like this all across India. It’s a microcosm of the macro divide—the upper middle class versus the lower classes; the city folks versus the rural folks. In some areas, you have large amounts of property, and in other areas, being well off means having a servant who also has a servant. Maybe due to my upbringing and my path, I feel empathy for these people of shared roots.

These trips back to India remind me that the "other half", these people who look like me, probably speak the same or similar languages, and share common ancestors—they’re the ones on the front end of the climate crisis. They too have hopes, dreams, and aspirations. I was given a once-in-a-lifetime shot because someone hired my dad as a postdoc in Kansas, and the rest is history. It changed the playing field for me. This opportunity has allowed me to live a life my ancestors could only dream of.

With this privilege comes a sense of responsibility. My upbringing and path have instilled in me an empathy for those who share my roots. I feel a moral obligation to give back and contribute positively to the world. The question I now grapple with is how best to use the opportunities I’ve been given to make a meaningful impact. It’s not just about individual success; it’s about leveraging my position to help others and create a legacy that benefits future generations. Life will continue, but so will the search for ways to bridge the divide and make a difference.